29 July 2016

Knowledge is POWER

As the saying goes, inquiring minds want to know, and there is perhaps no more an inquiring mind than Larry Smarr’s.

The founding director of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2), Smarr has spent a lifetime exploring everything from black holes to bacteria in our guts and then developing computational methods to explain these mind-bending phenomena.

His pursuits have led to some pretty idiosyncratic endeavors. To explore how complex ecosystems work, Smarr once built a 200-gallon coral reef tank in his living room. Twenty years later he is exploring the dynamic ecosystem of his own human body, monitoring it by collecting and evaluating his blood and stool samples on a regular basis.

Yes, he’s inquiring—and dedicated.

Smarr’s inquiries have taken many forms and ventured down myriad avenues, but his intellectual quests started at a very young age.

“I always knew I was going to be a scientist from the first grade because that was what I was interested in,” he said, recalling how all his classmates would look to him for help on science projects such as constructing a model of the solar system.

“Whether it was a natural interest or a natural aptitude, it’s hard to say,” he added.

Smarr’s parents, who ran a florist shop in Columbia, Mo. were “supportive but a bit mystified.”

“There was never any reason about what I would study,” he said. “I would stumble on something, and I’d think ‘I can do that.’ I’d learn about it, study it and then move onto something else.”

As a teenager living in a college town, with University of Missouri close by, Smarr had easy access to the university’s library and was already taking calculus classes at the college by his junior year of high school. When it came time to graduate, he received both a master’s degree and a bachelor of arts in physics—a point of pride for Smarr, especially when it came to his undergraduate degree.

“I was one of the first physics students to be allowed to earn a bachelor of arts and not a bachelor of science because I wanted to have more electives,” he said.

From there, Smarr received his Ph.D. in physics from the University of Texas using supercomputers to try to understand “dynamic, nonlinear coupled systems” from the astrophysics of giant galactic radio jets to the collision of black holes.

But in studying those systems, he realized that many other scientists could use supercomputing power to unlock a vast array of mysteries: from particle physics to living organisms to the universe. So Smarr worked with his colleagues to create the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he was a professor.

It was love of cross-disciplinary research that brought Smarr to UC San Diego in 2000 to help found and then serve as the director of Calit2, a UC San Diego/UC Irvine partnership. He also holds the Harry E. Gruber professorship in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at UC San Diego’s Jacobs School of Engineering.

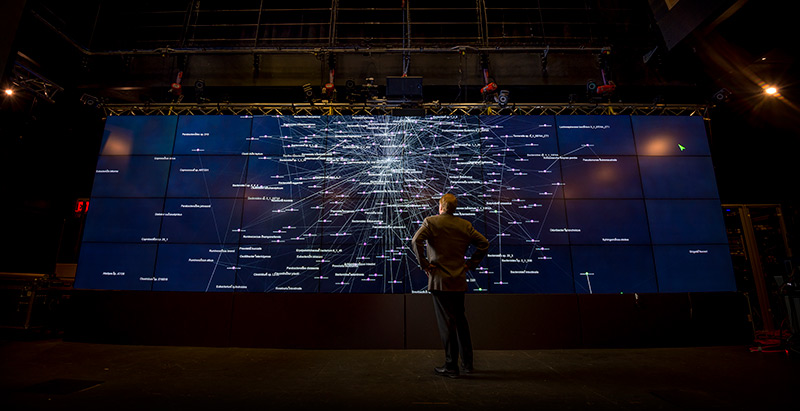

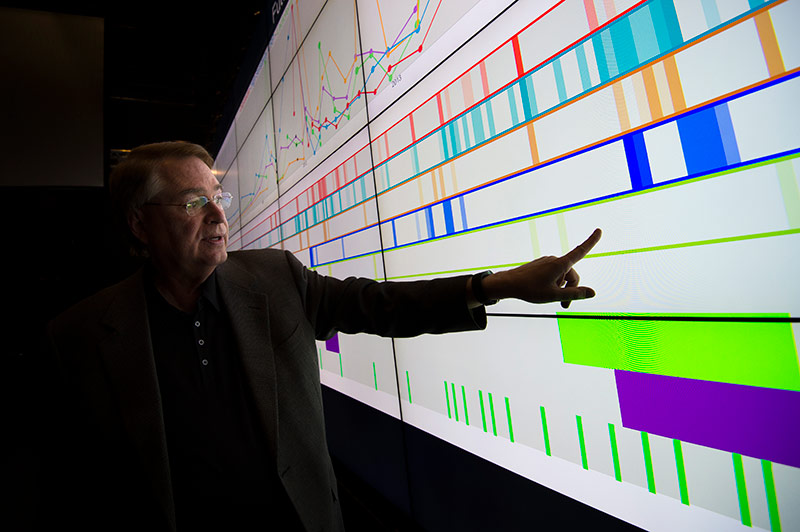

In these roles, Smarr used Calit2 to organize interdisciplinary teams to study the digital disruption of health, energy, the environment, and culture. He oversaw building leading-edge information infrastructure from supernetworks to virtual reality and scientific visualization—which is the ability to make scientific findings more understandable through scalable interactive visual formats.

Through his work in these various fields, it became clear to Smarr that he and other researchers needed a new “big data” cyberinfrastructure. Because of that he has taken the lead in creating the Pacific Research Platform, a high-powered “information superhighway” dedicated to research and education, interconnecting West Coast universities. The Pacific Research Platform is expected to give participating universities and other research institutions the ability to move data 1,000 times faster compared to speeds on today’s inter-campus shared internet—something that is vitally important to be able to make sense of the increasing amounts of data and information that scientists and others must analyze.

Take, for instance, the study of microbiomes, which are the large and varied collections of bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms that live both within and around us.

Although it is a massive area of study, Smarr has tackled the subject, in part, by using a very personal approach. For the past several years, Smarr has obsessively monitored his own body—with regular analysis of his blood and stool samples—to better understand the complex ecosystem that is the human body. Smarr calls this effort the “quantified self”—an endeavor that he believes will form the basis for future personalized precision medicine.

While studying his own bodily functions might seem routine, Smarr said it actually requires a large amount of computing power. The data generated by the genomic analysis of a single stool sample, for instance, is about 35 gigabytes of data—or about 5,000 times larger than a digital photo you take on your smartphone. To computationally analyze the dynamics of his microbiome over four years while comparing it to hundreds of other people’s microbiomes, both healthy and sick, he and his colleague Rob Knight, a professor in the Department of Pediatrics at UC San Diego with an additional appointment in the university’s Department of Computer Science, are currently burning through one million core-hours of supercomputer time on the San Diego Supercomputer Center. That is equivalent to running a laptop for over 100 years.

While Smarr and Knight have been on the forefront of computational microbiome research, many other groups are undertaking similarly large projects. In response, the White House announced a new National Microbiome Initiative in May to foster the integrated study of microbiomes across different ecosystems, with Knight and other UC San Diego scientists in attendance for the announcement.

“This is now ‘The Next Big Thing.’ The study of microbiomes has tremendous potential to provide insights into health, diseases, and agricultural and environmental sustainability,” Smarr said.

Still, Smarr marvels at the speed with which microbiome research has grown. Just ten years ago, the world of microbiomes was relatively unknown with the research focusing on environmental microbiomes such as those J. Craig Venter studied across the planet’s oceans.

“You recognize how quickly it all moves from basic research to a White House initiative,” Smarr said. “Every time I live through one of these transformations, it takes my breath away how fast innovation can move from the first germ of an idea.”

But unlike many who view innovation’s dizzying pace as a threat or a cause for concern, Smarr sees it as a hopeful sign.

“It makes me optimistic, considering the whole planet is facing a series of steep challenges,” he said.

Those challenges and the persistent race to face them will require everyone—not just scientists and researchers—to keep pace with change.

Because of that, Smarr said, San Diego is fortunate to have UC San Diego Extension and other continuing education institutions that are dedicated to helping people reskill and upskill.

“With the Extension program, San Diegans have the opportunity to participate and retrain themselves to better work in the future that is coming,” he said.

“My father spent his whole life in one job,” Smarr added. “Those days are gone forever. In a city as vibrant as San Diego, its citizens must be able to adapt. Change is never going to stop—it’s just going to accelerate.”