11 May 2017

Behind the Lens with Photographer Caity Fares

By Jill Esterbrooks

Portrait by Caity Fares

Without an oversized bag bulging with bulky cameras and a multitude of lenses, Caity Fares is not easily recognizable as an award-winning photographic artist.

Typing on the keys of her laptop computer with her cell phone within reach, the 29-year-old explained that these and other digital devices are among the most important tools for today’s amateur and professional photographers.

“More than ever before, photographers of all ages and skill levels are embracing technology—not only to create and manipulate images but also to promote their art and market their businesses,” said Fares, a San Diego-based visual artist and educator.

This intersection of technology, art and the evolution of photography are the themes that Fares explores in the various classes she teaches at UC San Diego Extension. It is a subject she knows all too well.

Imagined Landscapes Grid by Caity Fares

Flash Forward

Armed with digital, analog, and handmade cameras pieced together out of discarded materials, Fares has traveled the world from Indio, California, to Fljotstunga, Iceland, producing compelling images that range from traditional portraits to experimental landscapes.

“Timeless aesthetics such as horizon lines, skyscapes, and mountains inspire me, and I often make images that question what it means to look into the distance,” Fares wrote on her website, which also showcases eye-popping images created with colorful dyes on film and multiple exposures.

As a working artist, she is constantly producing new works and challenging herself to look at the world around her to capture the more sublime, surreal, and ephemeral images that abound in cityscapes and natural landscapes.

“For me it isn’t about the camera per se, but about training the eye and then using the box to capture the image,” she said.

This conscious mind-set and visual acuity has been a constant since her early childhood, when family road trips offered ample time to “contemplate the symbols and explore the poetry” of traveling around the scenic West.

Though she originally went to college with the goal of becoming a journalist, Fares eventually gravitated toward photography and the visual arts.

She’s still a prolific writer (particularly on art theory and criticism), but her driving passion and professional endeavors are now firmly rooted in photography.

That’s proven a smart career move. In the past decade, Fares’s photographic work has been shown in galleries and other venues throughout the United States and abroad (including Budapest), and her images have appeared in publications such as BLUR Magazine, F-Stop Magazine and the Los Angeles Times.

Untitled by Caity Fares

Teaching the Art of Photography

When not creating and exhibiting her own photographic art-works, Fares coaches and collaborates with a wide range of photography students—from college-going Gen Zers (postmillennials) and professional studio photographers to retirees looking to hone their hobby.

Fares teaches a variety of courses at UC San Diego Extension and will be one of the featured instructors for the new Specialized Certificate in Photographic Portraiture. Along with technical photographic instruction, the certificate program zooms in on the history of photographic portraiture and exposes participants to ways of establishing a portraiture business.

Fares is among the cohort of highly talented and widely respected portrait photographers and industry experts teaching courses in the certificate program, which Extension began offering in the spring due to student demand.

“Caity brings a fresh and forward-looking perspective to the program that blends cutting-edge artistic excellence with practical, hands-on instruction,” said Teresa Grosch, program manager at UC San Diego Extension.

Back to the Future

Fares may have an eye on the future of this ever-evolving art form, but she also gives a respectful nod to its storied past, which dates back to the 1880s.

She recently taught an Extension course on the history of photography, sharing with her students many of the visual art form’s major milestones—from daguerreotype to digital.

“History of photography is, in some sense, a history of the changing of technology,” said Fares, who earned a bachelor’s degree in art from UC Santa Cruz and a master’s of fine art in photography at the San Francisco Art Institute.

While her first camera was a digital model handed down from her father, she continues to experiment and create images with a variety of old-school and handmade equipment, including crude pinhole cameras built from mannequin heads.

Working in an image-saturated era with seemingly endless tech tools that edit and enhance, she offers photography students one of her own lessons—one that feels more like an “unlearning.”

“It has to do with the way we see the world, and with letting the camera capture the imperfections of our sight and banalities of our lives,” Fares said.

It was a “gift” she received while doing a residency in Iceland.

“I was living on a rural farm with nothing but antiquated equipment and vast open spaces,” she recalled. “It forced me to create art that came from quiet observations and endless studies of my surroundings.”

When students come to her feeling uncertain or lacking inspiration, she’ll share this story and tell them to “hit the pause button and look more closely at what you might take for granted every day.”

Often those encouraging words result in poignant and authentic images.

For instance, in a previous class, one of her students was a stay-at-home mom who felt frustrated because she couldn’t get out much and didn’t know what to photograph.

“I told her to refocus and see her home life through a different lens. Sure enough, she came back with some of the most beautiful photos of her sleeping children and amazing images of ordinary family life.”

Selfies and Social Change

There’s power in seeing, and in really looking, particularly in light of recent cultural and political events, Fares said.

From self-portraits posted on social media by gender-nonconforming teens to protestors capturing images of women’s marches and Black Lives Matter sit-ins, she said photographers today can engage in ways that would make French humanist photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson and Brazilian social documentary photographer Sebastiao Salgado proud.

This might be Fares’ second major lesson: by making images essential to the way people see themselves and others, photographers, for better or worse, change the fabric of American social life.

She plans to explore these and other heady concepts in her upcoming Extension courses such as Art of the Protest, and Variations on Photographic Portraiture.

“A portrait photograph can offer itself to a multitude of implications and interpretations, serving as a realistic representation of a person, a fictional narrative, or even an allegorical idea,” she said.

Snapshot of Portrait Photography

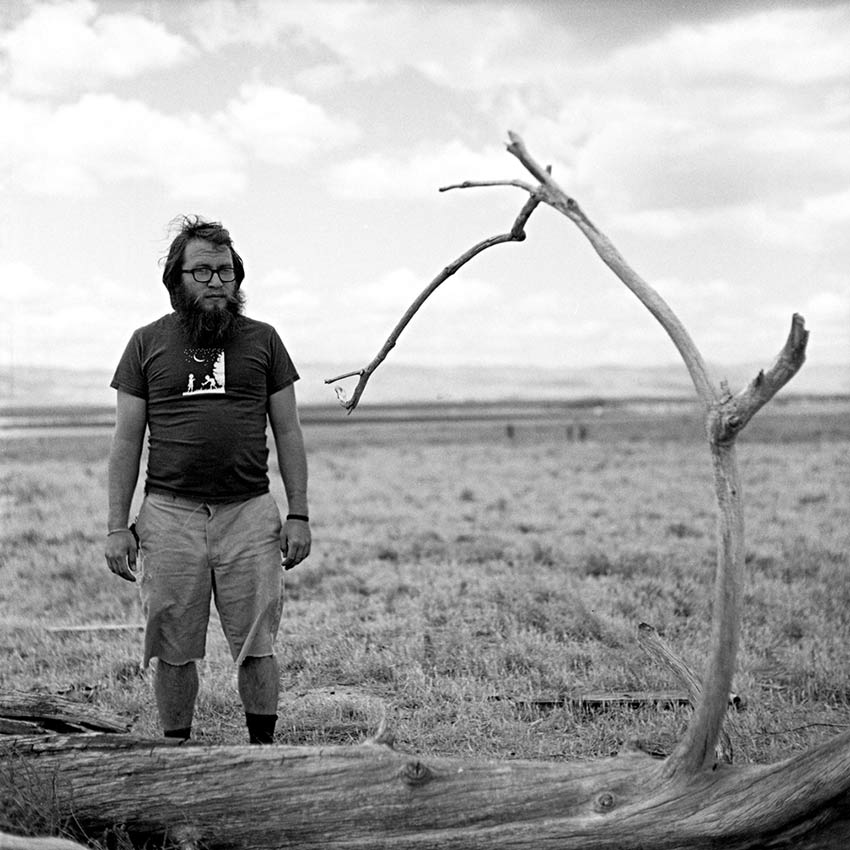

Jason, Somewhere East of Soledad by Caity Fares

Selfies may be the most popular type of portrait photography today, but the art form has a long history of embracing emerging technologies and producing iconic images—and it is a history that UC San Diego Extension’s new Specialized Certificate in Photography Portraiture explores in depth.

The invention of photography is credited to painter Louis Daguerre, who introduced the artistic concept to the French Academy of Sciences in 1839. That same year, American metal-worker-turned-photographer Robert Cornelius produced what is considered the first photographic self-portrait.

Throughout the 1840s, upstart photographers opened portrait studios in major US cities. To gain attention and dissuade public fears of this new medium, they captured images of well-known figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Charles Dickens.

Adam, Whiskey Hill by Caity Fares

In addition to photographs of rich and famous people, portrait photography became a way to preserve history. Native Americans visiting Washington, DC, in 1857 to conduct treaty and trade negotiations were photographed for news archives. And when the Civil War broke out in 1861, photographers began producing images of soldiers on the battlefields.

In addition to photographs of rich and famous people, portrait photography became a way to preserve history. Native Americans visiting Washington, DC, in 1857 to conduct treaty and trade negotiations were photographed for news archives. And when the Civil War broke out in 1861, photographers began producing images of soldiers on the battlefields.

Portrait photography also assisted in criminal investigations. In 1870, Allan Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency began photographing thugs and thieves, compiling the world’s largest collection of mugshots.

During the Great Depression, photographers began taking photos of families and individuals suffering from the economic disaster. Among the most recognized Dust Bowl photographers is Dorthea Lange, whose 1936 portrait "Migrant Mother" became the embodiment of a picture being worth a thousand words.

Portraits are a staple of modern photography— especially those of celebrities and pop-culture icons. Annie Leibovitz, a pioneer of celebrity portraiture photography, is known for her photos of rock stars and newsmakers from John Lennon to Bill Gates.

With the advent of smart phones and other digital devices, the tools and methods of portraiture and self-portrait photography may be changing, but there is little doubt that they continue to play a vital role in defining society and documenting history.

UC San Diego Extension offers a variety of programs and courses on photography including Photography: Images and Techniques and Photographic Portraiture. Learn more at https://extension.ucsd.edu/courses-and-programs/photography or contact the department at 858-534-5760 or ahl@ucsd.edu.